Bridging the Cultures of Japan and Florida

Expanding the Community Colony Members Disperse George Morikami’s Legacy

Establishing a Farming Colony in Faraway Florida

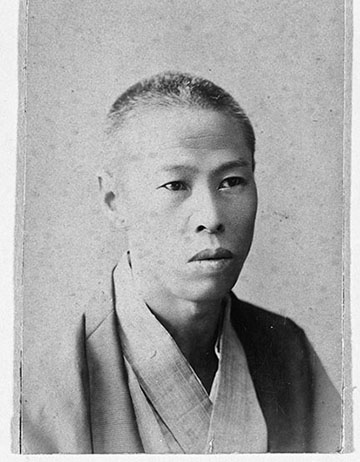

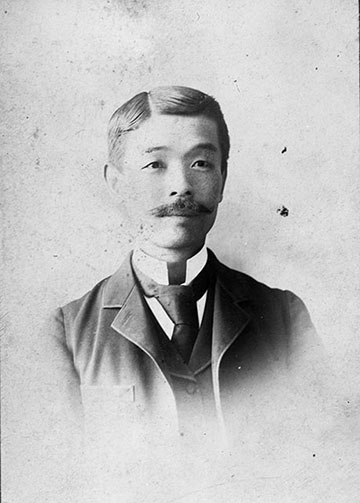

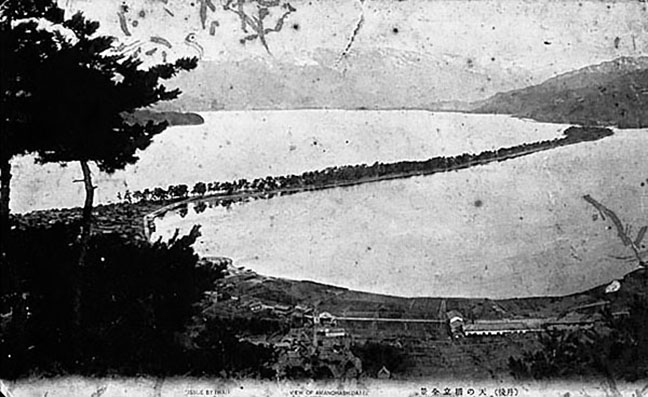

Japan ended its policy of isolation at the start of the Meiji period (1868-1912) signaling a major shift from the feudal society ruled by regional lords (daimyo) and samurai to a constitutional monarchy. This brought not only political, but also philosophical, economic, and scientific changes throughout the country. In order to enhance these changes, the Japanese government began encouraging young men to study abroad at foreign universities. One such man was Kamosu, later called Jo, Sakai born in the town of Miyazu, October 7, 1874. Starting in 1895, he attended New York University and was a member of their first graduating class from the School of Commerce, Accounting and Finance in 1903.

After graduation, Sakai began visiting possible farming colony sites in California, Texas, and Florida. He met with Florida Governor William Jennings (1863-1920) and James Ingraham (1850-1924), the president of Henry Flagler’s Model Land Company. They eagerly offered their support for the new agricultural techniques and crops that Sakai promised his settlers would introduce. On Christmas Day 1903, he first saw the site at Boca Raton that would become the Yamato Colony.

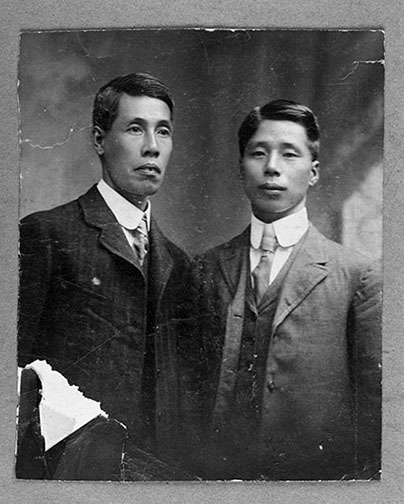

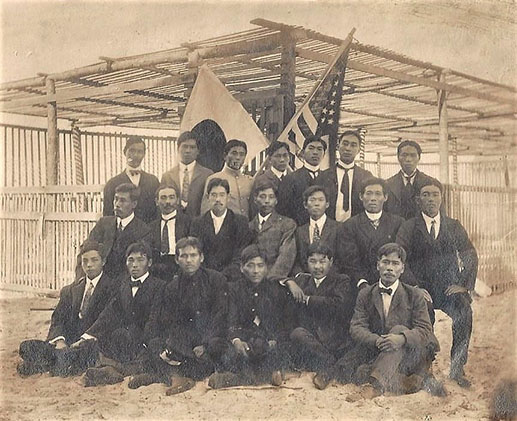

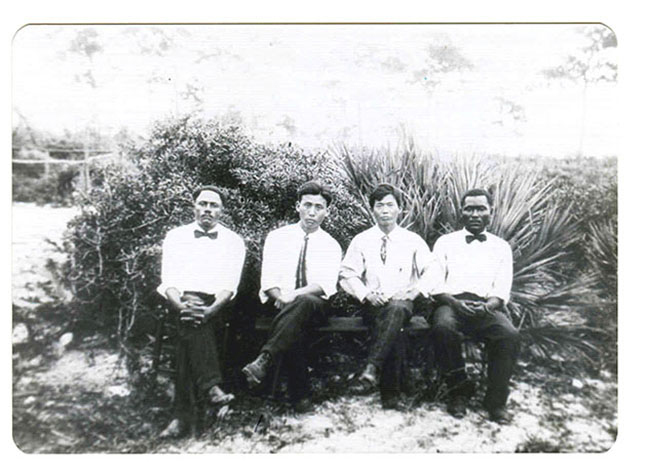

Masakuni Okudaira (1880-1940), a member of an influential noble family in Nakatsu who had graduated from Yale, was highly influential in starting the colony. After a couple of years and with the help of more than 20 ambitious young men from different parts of Japan, they formed the colony and began the difficult work of clearing and farming the land. Mitsusaburo Oki (1855-1906), brother-in-law of Jo Sakai, was an important participant and a principal investor. He amassed his wealth in the silk crepe (chirimen) wholesale business in Kyoto prefecture. There were three brothers in the Sakai family, the oldest was Masuji, then Jo, and Tamemasu who was adopted as heir to the Kamiya family and went by the name of Henry in Florida. Another key member born Sukeji Morikami (1886-1976) but known as “George” in Florida, arrived from Miyazu in 1906.

They chose the name, “Yamato,” for the farming colony. The characters, 大和, mean “great peace.” It was also the name used for the main island of Honshu in ancient times. A crucial element in Sakai’s plan was that his settlers would all be landowners, not just laborers; unlike the many Japanese immigrants flowing into sugarcane plantations in the kingdom of Hawai’i (statehood was not until 1959). The Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907-1908, a series of informal papers signed by Japan and the U.S., underscored this point by stipulating that no passports would be issued to laborers emigrating to the U.S.

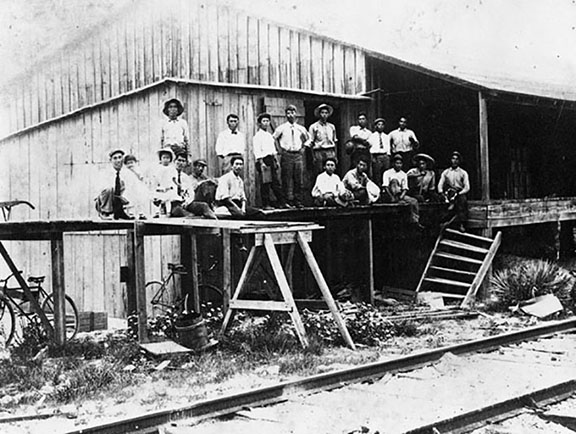

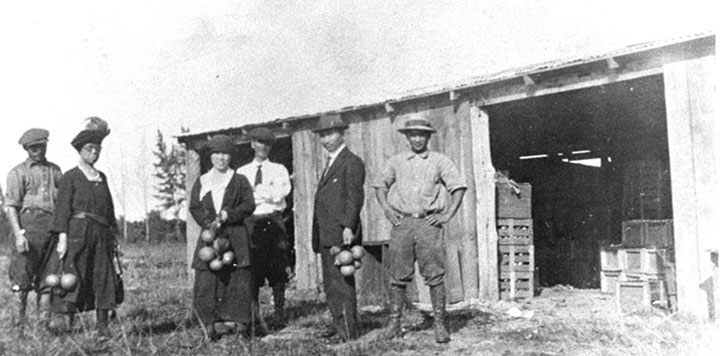

Bringing agricultural innovation to South Florida was another important element for the success of the colony. Plants like Formosa tea and mulberry bushes as well as sericulture (silk cultivation) were some of the advances they attempted. In 1908, the Yamato Colony reported in a Japanese American newspaper published in New York that they had successfully planted more than 42 acres devoted to pineapple cultivation. Later, due to being out-priced by pineapples imported from Cuba, they switched to other vegetables like alfalfa, cabbages, cucumber, eggplants, peppers, string beans, squash, turnips, and tomatoes.

Expanding the Community

The best way for establishing the farming colony was to encourage family life. At its height, there were 17 families with diverse backgrounds living at Yamato. The first parents to settle at the colony were Akila and Iola Ohnishi who brought with them their daughter, Sumile Grace Ohnishi age seven, plus two children from a previous marriage. Their son Akila Hada Ohnishi, Jr. was born at Yamato in 1906. It was 1907 when Jo Sakai went back to Japan to marry Sada (nee’ Kawashima), where they met for the first time shortly before the wedding. They raised five daughters at Yamato.

Yoshikazu Wilson Yamauchi was born to Jinzo and Naka Yamauchi in Boca Raton in 1917. Yoshikazu lived at the colony until he was 11. Another wedding took place in Japan in 1922 when Oscar Susumu Kobayashi wed Suye (nee’ Matsumoto), and they had three children in Yamato. As one of the later brides, Suye was told not to bother packing her kimono. Instead, all of the women adopted western style dress, which was better suited to the Florida climate and farming conditions. During this time settlers would regularly gather for games and socializing, but the young bachelors like Sukeji Morikami (1886-1976) – who went by the name “George” in Florida – would only join in for special celebrations such as New Year observances.

Yetsu (nee’ Oishi) Kamiya married Henry Tamemasu Kamiya in 1909. The Kamiya family grew to be the largest with six children. Henry Kamiya was actually a younger brother of Jo Sakai, but he had been adopted into another family as heir (a common practice in Japan at the time). Don Ikumo Oishi, another prominent member of the farming colony, was Yetsu Kamiya’s brother. He remained in Florida and lived in the Jacksonville area until his passing in 1972.

The Kamiya family owned a convenience store and gas station on Dixie Highway. These stores along with the train depot, post office, and schoolhouse, made-up the village of Yamato that serviced not only the colony members but also their neighbors in Delray Beach and Boca Raton. Laurence Gould – the famous explorer who traveled with Adm. Byrd – was the first teacher at the public schoolhouse, followed by Molly Monroe, L. Klein, Clementine Brown, and Bly Davis. Children of the Sakai, Kamiya, and Kobayashi families all attended Delray Beach High School.

Fishing was a favorite pastime among the men, while the children would catch crabs and lobsters when they went to the beach. Families and individuals gathered for beach parties at a spot that came to be known as, ‘Yamato Rocks.’ Most of the families attended Delray Methodist Church (now Cason Methodist Church). All the locals helped one another through difficult times, such as clearing land and hurricane recovery.

Colony Members Disperse

One of the first big losses for the Yamato colony was the passing of their main financial sponsor Mitsusaburo Oki in 1906 from malaria. Later in 1914, a fire destroyed Henry Kamiya’s house. They would eventually move into the house occupied by the Sakai family, after Sada Sakai and her daughters returned to Japan and Mrs. Kamiya’s brother, Don, moved into their old house.

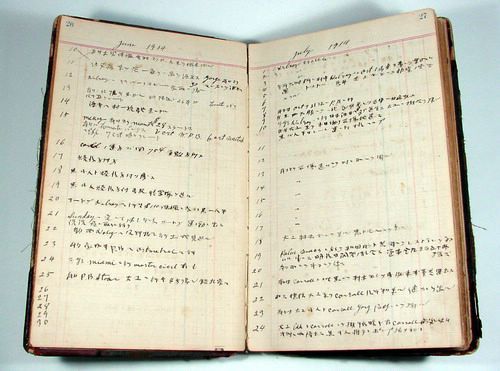

The house fire prompted Kamiya to start keeping a diary of mundane farming tasks, important events in the colony, and international incidents, which continued until 1941. This diary is an invaluable source for information of the day-to-day activities involved in running a large farm as well as important events that took place at home and abroad. One of the more moving entries included the passing of Jo Sakai in 1923. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis on July 21 and was moved by train to a sanatorium in Asheville (NC). One month later, he passed from complications during treatment. Responsibility for the community passed to his younger brother Henry Tamemasu Kamiya.

At the same time, the Florida real estate boom of the early 1920s was spurring the shift from farming to resort communities in South Florida. Many settlers took advantage of this and sold their land moving to other places in the U.S. or returning to Japan. Oscar Kobayashi moved his family to the Chicago area in 1925, then to California in 1939. Hideo Kobayashi even became a local real estate broker for a few years. Swiftly following the boom was the contraction of the banking system in 1926. Small, local banks like those in Delray Beach closed and Sukeji Morikami (1886-1976) – who went by “George” – and other colonists lost nearly all their wealth overnight.

Kamiya’s diary ends in the summer of 1941, shortly after the last Japanese dignitaries – representatives from the Japan Railroad Ministry – visited the colony, and the news had reached South Florida of a pending oil embargo meant to cut-off key resources as retaliation for Japan invading Indochina. By the start of World War II, only two families and four individuals remained from the original farming colony. Not long after the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, fueling anti-Japanese sentiments, the U.S. government froze the assets of Japanese citizens including those of George Morikami and Henry Kamiya.

Next, in order to create a new Army Air Corp. training base, the Federal government confiscated over 6,000 acres. Hideo Kobayashi, along with other minority residents in the area, lost his home. He found an eviction notice posted to the door of his home in 1941. Army personnel would eventually turn the Kamiya house into their headquarters. This marked the end of Yamato as an experimental farming colony.

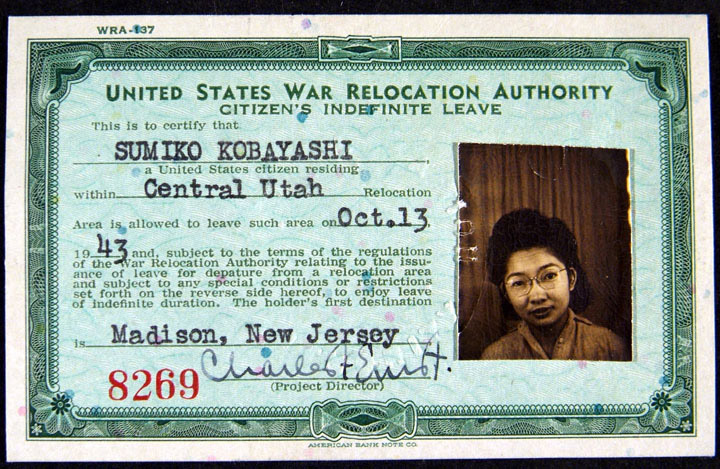

Some of the colonists who moved to the western U.S. were incarcerated along with 120,000 others of Japanese descent who ended up in one of 10 camps or other U.S. Justice Department and Army prisons. Among those interned 2/3 were U.S. citizens by birth. From the Yamato colony: Oscar Kobayashi and his family were sent to Topaz (UT), Riichi Morita and his family were in Minidoka (ID), and Henry Kamiya had gone to visit his daughter Masa’s family in California when they were all interned at Manzanar (CA). The family of Oscar Kobayashi donated his traveling case to the Morikami Museum’s permanent collection. He had the case when he arrived at Yamato in 1914, and it was one of the few personal possessions he was able to keep while interned at Topaz. Sumiko Kobayashi was among the students who were permitted to leave camp to continue their education. She studied in New Jersey and became a computer analyst.

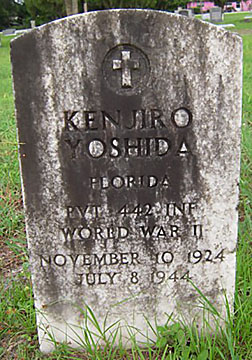

Those that remained in Florida faced various levels of discrimination such as being denied haircuts, to even being deprived of seeds and fertilizer. Mr. Kobayashi who had established a successful landscaping business in Ft. Lauderdale had to obtain written permission every time he crossed county lines, although his children (being born in the U.S.) did not. He eventually moved to Ft. Lauderdale where he lived until his passing in 1967. Kenjiro Yoshida, born at the Yamato colony, died in Italy serving his country with the highly decorated 442nd Infantry Regiment. In addition, Tamotsu (Tom) Kobayashi served in the Occupation Army in Okinawa from 1946.

George Sukeji Morikami’s Legacy

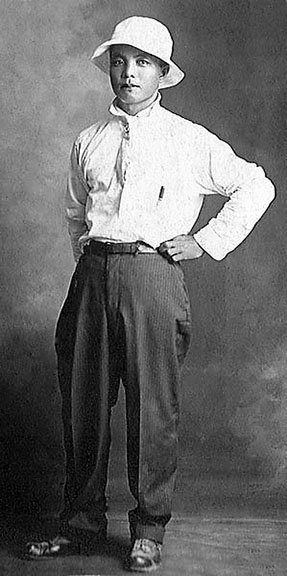

The two remaining bachelors of the colony were Shohbi Kamikama (1889-1974) and Sukeji Morikami (1886-1976), affectionately known as “George.” George remained in Palm Beach County but moved further north of the original Yamato site into Delray Beach. Throughout his life in Florida, George experienced many highs and lows. Starting with his choice to come to America. As the eldest son of a farmer, he fell in love with a young woman called Hatsu Onizawa. He proposed marriage, but her parents did not approve. With a broken heart, he resolved to go to Florida.

After weeks on a ship and on trains, the weary traveler arrived on May 4, 1906 at 9:15 PM. Mitsusaburo Oki agreed to be George’s financial sponsor, paying his travel expenses to get to America, and promising him $500 with which to return home when his three-year contract was complete. With the passing of Mr. Oki less than seven months after his arrival, George found himself penniless in a foreign country and his entire future in jeopardy.

George decided to move to Eau Gallie, Florida, in 1909. With the help of Mr. Minoru Ohi, he enrolled in the local elementary school as a 5th grader where, with much hard work, he was able to improve his English skills and graduate. While living in Mr. Ohi’s home he received word that his beloved Hatsu Onizawa had married and his dream of going home a wealthy man to take her hand in marriage and start a fruit orchard was no more.

He returned to Delray Beach in 1910. Thanks to a friend who allowed him to farm 1/2 an acre of land and to some local retailers who let him buy on credit, he was able to turn a profit off the harvest from this small patch of land. Being resourceful, he looked for new sources of revenue and soon started a mail-order wholesale vegetable business. This became a great success. After emergency surgery in Miami to treat an ulcer, he recovered and continued to build his fortune only to loose it all when the local banks collapsed after the real estate boom in 1926.

He slowly rebuilt his wealth, again, only to have his assets frozen during the war years. After gradually restoring his real estate portfolio and living a very frugal lifestyle, he was once again prospering. He made his one and only trip back to Japan in 1960. George’s sister Fude married into the Ida family and her son, Kazuaki Ida, still lives in the ancestral home today.

George had considered becoming a citizen for many years. It was not until the Immigration (or McCarran–Walter) Act of 1952 that any person born in Japan could become a U.S. citizen. In a letter from George to his niece Reiko Okamoto he wrote, “For what I have now, both directly and indirectly…I owe this country.” George finally naturalized on December 15, 1967.

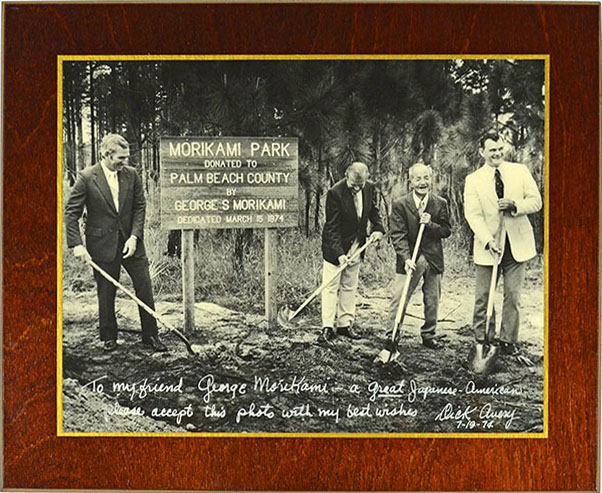

Now that he had achieved his dream of citizenship, he wanted the people in his adopted home to remember the name Morikami. With the help of Japanese friends living in Miami, Mr. James (Shunji) and Mrs. Chieko Mihori – who remain kind supporters of the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens – George generously donated all of his nearly 200 acres of land to the people and county of Palm Beach in 1974. That land is now our park, museum, and beautiful Roji-en gardens. He wrote to his niece:

I am 80 years old and yet I plant trees. People may laugh at my foolishness. Although I

might be foolish, this is my life’s desire, my dream. If I can plant something today, I will

have no regrets if I die tomorrow.

George passed away at his humble home on February 29, 1976. From unassuming origins in his hometown of Miyazu, suffering a broken heart, broken bones, battling the harsh environment and starting his own farm, to the busts and booms of the Florida economy, George’s perseverance and patience are an encouraging lesson for all of us.

Funded in part by PNC Art Alive, The Japan Foundation, New York / Center for Global Partnership and the Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Charitable Foundation.