Misty Day at Nikko

Misty Day at Nikko

By Yoshida Hiroshi (1876-1950)

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Shōwa period, 1937

16”h x 11”w

Gift of Mrs. Ruth B. and Dr. Julius N. Obin

2011.014.009

The Nikko pilgrimage route in Tochigi prefecture began as a path used primarily by esoteric monks traveling between the temples in Nikko. When Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616) – founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate – passed away, Tōshōgu Shrine was built there as a mausoleum and the ruling government created better roads for people to travel from Edo to Nikko to pay respects. In this print, Yoshida depicts three junreisha, or pilgrims, paused at stone steps to one of the smaller shrines located along the way to the grand Tōshōgu. Surrounded by immense cedars, tops disappearing into the mist, the artist creates both a sense of sublime silence and comparative perspective, the pilgrims’ relatively small scale emphasizes their significance as, no more or less than, the scattered stones upon which they rest.

A Journey to the Waterfalls

A Journey to the Waterfalls in All the Provinces: Yoshitsune Horse-Washing Falls (Shokoku taki-meguri: Yoshitsune umaarai no taki)

By Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849)

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Edo period, ca. 1832

14.25”h x 9.5”w

Purchase funded by Members of the Wisdom Ring

2018.001.003

Reverence for nature has long been celebrated in the visual arts of Japan. Artists such as Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) were masters at capturing the majesty of the steep mountains, rushing rivers and stormy seas that defined the islands of Japan. In Hokusai’s A Journey to the Waterfalls in All the Provinces, a set of eight woodblock print designs issued during the years 1833 and 1834, the artist explores the power and mystery of Japan’s revered waterfalls. One of the most effective and intimate compositions of the series is better known as Yoshitsune Horse-Washing Falls. This waterfall takes its name from a famous episode of medieval history when the tragic 12th century hero Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159-1189) bathed his favorite mount, Tayūguro, at this spot in the mountains of Yoshino. In this composition, the waterfall itself symbolizes the strength and endurance of the samurai.

Untitled I & II

Untitled I & II

By Suhama Tomoko (b. 1965)

Glazed stoneware

Heisei Period, 2013

Left: 16.5” h x 14.5”diam; right: 11.5”h x 10.5”diam

Gift of Kevin and Doris Hurley

2016.008.001-.002

Born in Hyōgo, Japan, Suhama Tomoko was educated at Kyoto Art University and studied under Suzuki Osamu (1926-2001), one of the founders of Sōdeisha, a group of avant-garde ceramic artists formed in 1948. Rebelling against traditional ceramic conventions, Sōdeisha members were interested in exploring biomorphic and geometric, slab-built sculptural forms. Suhama’s playful ceramic spheres show strong influence of the Sōdeisha movement. The artist describes these coil-built, hollow forms as “shells of air.” The matte blue-green barium glaze produces a soft and sensuous quality that belies the hard, rigid outer surface. The uplifted layers slowly peeling away from the central forms give a sense of animation to the works, as if they are engaged in delightful conversation.

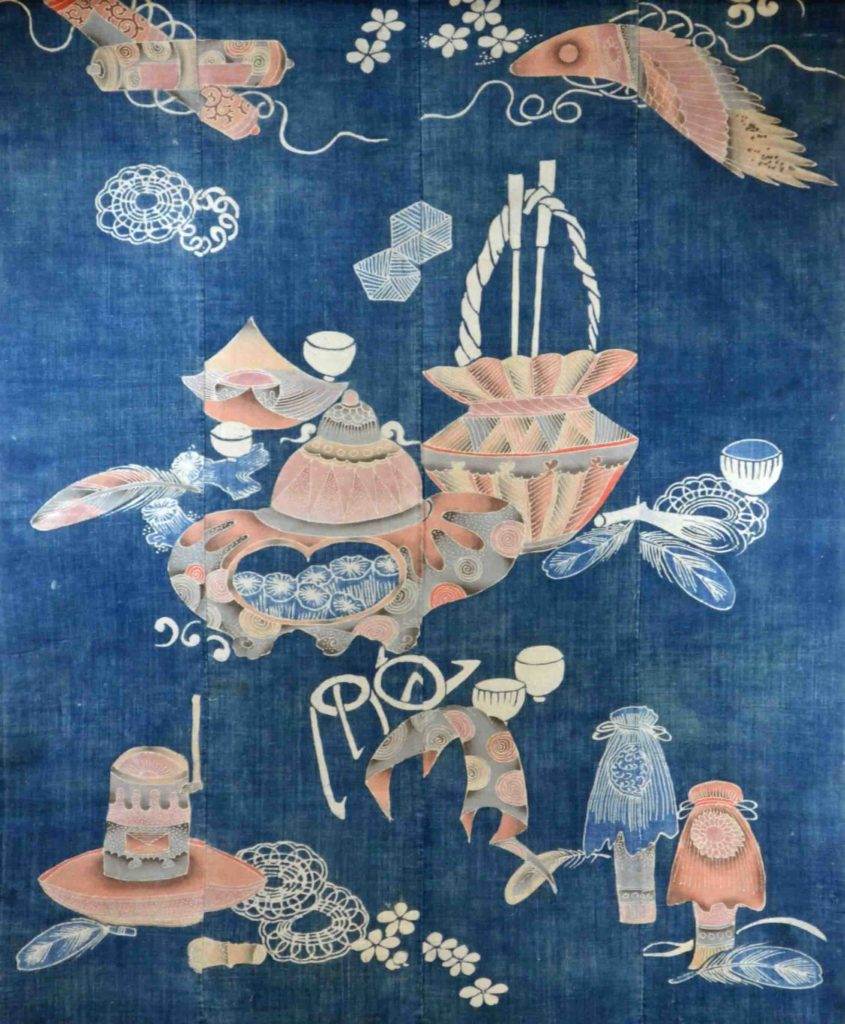

Bridal Sleeping Cover (Futonji)

Bridal Sleeping Cover (Futonji)

Hand-painted (tsutsugaki) resist-dyed cotton, indigo, and other pigments

Meiji period, ca. 1870

61.5”h x 50.5”w

Museum purchase

2016.006.001

The Japanese tea ceremony, or chanoyu, developed as a subculture of Zen Buddhism among the samurai in the 16th century and later among townspeople. In the simple art of wabicha, originated by Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591), the host carefully selects a few humble tea articles appropriate for the season and occasion. In time, tea classes became fashionable training for young girls, and tea-related objects became an occasional decoration for bridal bed covers, especially on the island of Shikoku. On this futonji, a charming selection of tea utensils (dogū), including a charcoal brazier and basket, a tea grinder, tea whisks, and tea bowls, dance across the indigo ground.

Minguren I

Minguren I

By George Nakashima (1905-1990)

American walnut

1990

15”h x 61.5”l x 31.5”w

Gift of the Yasushi Stephen Yamamoto Estate

2020.005.001

The recent gift of this stunning Nakashima coffee table from the Estate of Yasushi Stephen Yamamoto (1943-2019) holds special significance for the mission of the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens and its commitment to the research, documentation, and interpretation of the Japanese American experience. Mr. Yamamoto was born on August 6, 1943 to Japanese American parents who had been forcibly interned at the Topaz relocation camp in Utah after the signing of Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. Overcoming severe deprivation and many obstacles, Steve and his family were eventually able to settle in Wisconsin. He earned a PhD in chemistry and had a long, successful career working for Dupont. Mr. Yamamoto retired in Palm Beach County and filled his home with art and objects that reflected his connection to his Japanese ancestry, including this table designed for him by Nakashima. The story of George Nakashima and his own family’s experience of internment at Minidoka in Idaho, must have been particularly meaningful. After receiving a diagnosis of cancer, Mr. Yamamoto often sought respite from the illness by visiting the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens. He was inspired to create the same sense of peace at his home and hired Hoichi Kurisu, designer of the Morikami gardens, to install a healing garden in his backyard. When the time came to consider his estate, he wanted to make sure that the extraordinary work and accomplishments of George Nakashima would find a new home and become part of the legacy of another accomplished Japanese American, Sukeji George Morikami.

Learn more about the legacy of the Yamato Colony.

White Foaming Wave (Nami Shibuki)

White Foaming Wave (Nami Shibuki)

By Watanabe Setsuo (b. 1947)

Stoneware

Heisei period, 2002

3.5”h x 4.75”diam

Gift of the Artist

2002.022.002

This unglazed tea bowl, or chawan, is made from the unique clay found in the area of Bizen, a city located in Okayama prefecture and one of the original so-called Six Old Kilns sites, which flourished in the 16th century. While unglazed ceramics were largely relegated to utilitarian wares by the 17th century, the irregular and rustic nature of Bizen wares continued to be favored for use in the tea ceremony, and are still considered one of the most distinctive and admired ceramics in Japan. Watanabe Setsuo’s winter chawan is a stunning example of the austere beauty characteristic of Bizen wares. Areas of reddish-brown, gunmetal grey, deep purple, and rivulets of natural ash glaze are chemical reactions that occur during the wood-firing process. This work is also a wonderful manifestation of the artist’s desire to imbue each vessel with a unique, innovative spirit while observing the centuries-old forms of traditional pottery. Tea utensils are often given a poetic name (gomei), which is meant to metaphorically celebrate the individual characteristics of the object. During a tea gathering, the gomei becomes a special conversation point between the host and guests. In recognition of Watanabe’s work, on October 25, 2011, Harada Shodo Roshi, abbot of Sogenji, Okayama, bestowed this chawan with the poetic name “Nami Shibuki,” or “White Foaming Wave.”

Ainu Coat (Attus)

Ainu Coat (Attus)

Appliqué and embroidery on plain weave elm bark fiber and cotton

Late Edo or early Meiji period, 1850-1900

50”h x 45”w

Museum purchase with funds from The Chisolm Foundation

2019.011.001

This Ainu coat was first acquired by Joseph H. Ehlers while serving in Japan as Engineering Trade Commissioner and Acting Commercial Attaché to the American Embassy from 1926 to1930. In his book, Far Horizons: The Travel Diary of an Engineer, he documents the details of a trip to Hokkaidō in autumn of 1927.He and a companion were invited into an Ainu home by a “swarthy dignified old patriarch with long hair and a full thick gray beard,” where he notes the “Many swords and knives and a bearskin bag hang on the walls. Outside are nine bear skulls, which play an important role in Ainu religious ritual.” Travel to Hokkaidō by westerners was still rare at this time and Mr. Ehlers probably received this treasured garment as a gift during his stay.The Ainu are a distinct cultural and linguistic ethnic group who reside primarily on the northern island of Hokkaidō. In traditional Ainu society, women were responsible for the making of clothing. The most common garments, known as attus, were woven from elm fiber and embellished on the surface with complex, symmetrical patterns created by intricate appliqué and embroidery. This stunning coat includes examples of several of these techniques.The ovoid motif in the embroidery pattern is called chik noka (eye form); the other is a curling, thorn-like form called moreau, created here by narrow appliqué strips of indigo cotton. Design elements are combined and interconnected, primarily at the neckline, hem, and sleeve openings. These mesh-like patterns are believed to derive from ancient images of tied ropes and fishing nets. Their placement at vulnerable openings in the garment is thought to offer symbolic protection for the wearer.

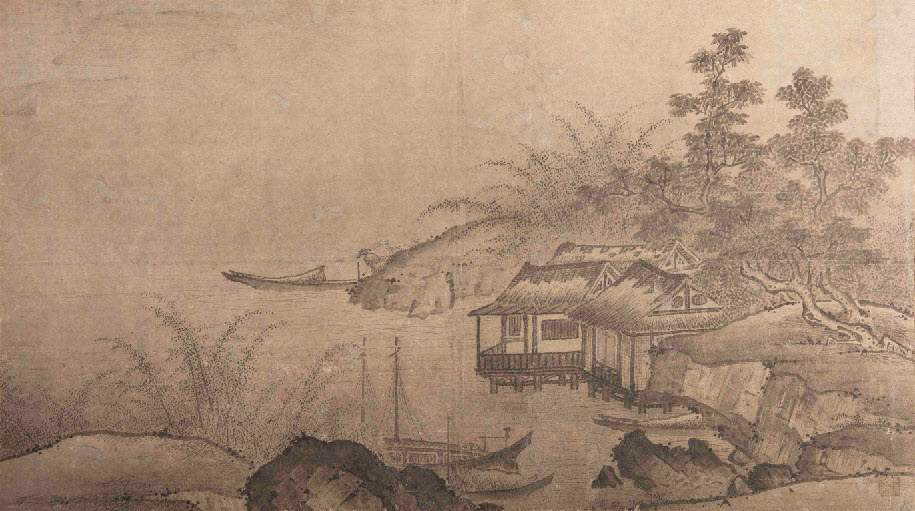

Fishing Village at First Light

Fishing Village at First Light

School of Kenkō Shōkei

Two-fold screen painting; ink on paper

Muromachi period, ca. 1500

25.25”h x 43.75”w

Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation

2015.006.002

In 2015, the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens was honored to receive a generous gift of over two hundred works of Japanese art from the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation. Mary Griggs Burke (1916-2012) and her husband, Jackson Burke (1908-1975) – discerning New York collectors – built what is widely regarded as the finest and most encompassing private collection of Japanese art outside of Japan. Mrs. Burke, who had a winter home in Hobe Sound, visited the Morikami frequently from its humble beginning in 1977. When the main museum building was constructed in 1993, she agreed personally to curate the inaugural exhibition by selecting works from her internationally renowned private collection. This lovely screen was cherished by Mrs. Burke, who once reflected, “I was, and still am, most deeply moved by Muromachi ink paintings.” Inspired by Zen Buddhism, these paintings were characterized by monochrome ink, or suibokuga. In Japan, early practitioners of suibokuga were Zen monks, some of whom traveled to China to learn the art. Technical characteristics of ink painting made it an ideal medium for the spontaneous and spiritual expression of Zen. As Zen ink painting was assimilated into Japanese culture, it became increasingly secular. Landscape themes, like this one, began to dominate the genre. By the late 15th century, suibokuga emphasized aesthetic appeal over spiritual content and had become a dominant influence on mainstream Japanese art.

Furisode

Furisode

Yūzen dyed silk crepe (chirimen), silk and gold embroidery, gold paint, cotton padding

Shōwa period, c. 1930

67.75”h x 51.25”w

Gift of Broward College

2018.008.004

Furisode is a formal kimono with long, sweeping sleeves and a lightly padded hem, traditionally worn by young, unmarried women for major social functions such as weddings and tea ceremonies. This furisode is an outstanding example of the highly refined level of textile design achieved through the intricate process of yūzen-zome, a hand-painted, rice-paste resist dye technique named after the fan painter, Miyasaki Yūzen (1654-1736). Application by hand allows for subtle gradations in color and unsurpassed sophistication in composition. In essence, the entire surface of this garment has become the canvas for a three-dimensional landscape painting depicting scenes from Heian period (794-1185) court life against a lyrical autumn backdrop of floating clouds, falling maple leaves, and cascading waters. Japanese clothing and textile design has a long tradition of incorporating the romantic escapades of the cultured Heian aristocracy, made popular by novels such as the Tale of Genji, written by Lady Murasaki Shikibu (978-1014). These motifs imply the wearer’s sophistication and knowledge of literary history and are considered particularly auspicious references for any aspiring young ‘princess.’

Funded in part by PNC Art Alive, The Japan Foundation, New York / Center for Global Partnership and the Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Charitable Foundation.