Votive Plaque (Ema)

Votive Plaque (Ema)

Ink and pigment on wood

Taishō period, ca. 1920

29.5”h x 23.75”w

Gift of Thomas Winant

2006.011.001

Ema (picture-horse) are boldly painted votive plaques that have remained an integral and dynamic art form within the Japanese Shintō belief system for many centuries. Horses are considered the favorite mount of the gods, or kami. Originally, members of the aristocracy and military elite would present a horse to a Shintō shrine as a sacred offering, usually accompanied by a specific request for assistance from the gods or protection. Eventually, real horses were replaced by a painting of a horse depicted on a fine-grained piece of wood rendered in the stylized shape of a stable with a pitched roof.

During the Muromachi period (1338-1568) the subject matter of ema expanded dramatically to include images of heroic warriors, figures from Shintō and Buddhist iconography, animals of the zodiac, and auspicious symbols representing the donors’ hopes for good health and prosperity. The depiction of sumō wrestlers also became quite popular. Sumō is believed to have originated in Japan in 23 B.C.E. when the emperor requested that two citizens settle their dispute by wrestling one another. The earliest matches were performed as a kind of ritual at agricultural festivals associated with Shintō beliefs. In the 17th century, sumō developed as a competitive sport where highly trained wrestlers (sumōtori) match body mass, physical agility, and mental concentration against one another in a sanctioned ring (dohyō). This example depicts a robust competitor wearing the traditional ceremonial keshō-mawashi around his waist. The characters in the upper left read “yokozuna” (champion) and “dohyō-iri” (ring ceremony). The petitioner of an ema with an image of sumō is most likely seeking strength or victory in some aspect of their life.

Plum Blossoms

Plum Blossoms

By Taki Katei (1830-1901)

Ink on silk

Late Edo or Early Meiji period, late 19th c.

84.5”h x 28.25”w

Museum Purchase funded by members of the

Wisdom Ring and Mr. & Mrs. Walter May

2006.041.002a-b

In classical Japan, the plum blossom was the iconic symbol of ephemeral beauty. In medieval times it was replaced by the now ubiquitous cherry blossom. Here the artist, Taki Katei (1830-1901), is harkening back to the classical aesthetics of Japan’s collective past. Taki was born the son of a samurai and studied both Japanese and Chinese style painting. His mastery of the brush is evident in the combination of soft, washes in the trunk of the tree compared to the hard, decisive lines of the smaller branches, as well as his use of negative space (areas with no paint). Taki was one of the Japanese artists that took part in the international Vienna Exposition of 1873.

Funerary Fragment (Haniwa)

Funerary Fragment (Haniwa)

Pigment on earthenware

Kofun period, 4th or 5th century

6.5”h x 4.75”dia

Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation

2015.006.057

Haniwa (rings of clay) are cylindrical clay sculptures representing humans, horses, houses, weapons, and other ceremonial objects that were placed around the mounds of imperial tombs in Japan throughout the Kofun period (ca. 300-600 C.E.). The intricate detail found on these objects contains an extraordinary insight into the material culture of Japan’s pre-Buddhist history, including various types of clothing and adornment, secular and religious utensils, and even symbolic physical gestures and dance forms.

This haniwa bust is part of a collection generously gifted to the Morikami Museum by Mary Griggs Burke (1916-2012) and her husband, Jackson Burke (1908-1975). Discerning New York collectors, together they built what is widely regarded as the finest and most encompassing private collection of Japanese art outside of Japan. Although there were few archeological objects in the collection, Mary Griggs Burke recognized the importance of including these enigmatic haniwa in her visual chronicle of Japanese art and culture and their connection to the later figurative architectural features of Buddhist temples.

Lidded Boxes

Group of four lidded boxes

By Mizuuchi Kyōhei (1910-2001)

Lacquered wood with gold and shell inlay

Shōwa and Heisei periods, 1981-1993

4”-7.75”w x 6.5”-10.5”l

Gift of Dr. Joel N. Ehrenkranz in memory of Elaine Ehrenkranz

2013.009.018-.021a-b

Elaine Ehrenkranz (1931-2008) was a well-known collector of Japanese lacquer boxes who compiled a comprehensive collection over many years. As a painter herself, she could spot the most balanced compositions and intricate designs, while still appreciating the overall shape and function of the original containers. She fully appreciated the material of all-natural lacquer, which is derived from the sap of the lacquer tree. Throughout the centuries, Asian artists have developed many different decorative techniques for lacquer wares. A few of them are represented here, such as: layered cinnabar (tsuishu), carved down inlay (chōshitsu), and the uniquely Japanese ‘sprinkled-picture’ (maki-e) – all techniques that take decades to master. Mizuuchi hand-signed each of these boxes, which indicates an intentional shift from anonymous utilitarian objects to fine art imbued with personal expression.

Festival Robe

Festival Robe

Rice paste, resist-dyed plain-weave cotton

Meiji period, ca. 1900

68.5”h x 49”w

Museum purchase funded by Members of the Wisdom Ring

2014.005.001

In traditional Japanese culture, it is believed that garments decorated with protective spirits will bring the wearer closer to the strengths symbolized by the auspicious motifs. The large, menacing spider enveloping this festival robe is a reference to the mythological race of monstrous arachnids known as tsuchigumo. A popular subject of Nō and Kabuki drama, the great spider and his army terrorize the legendary warrior known as Minamoto no Yorimitsu (994-1021) until they are ultimately vanquished by the hero’s mighty sword. Characters along the front opening of the robe read “Okuyama,” which is both a family name and a place name.

During festivals, individuals belonging to a specific trade or company wear similar garments to express group identity. This particular robe belonged to an employee of a rickshaw business. Typical of festival clothing, the design on this robe was created by a free-hand, rice paste resist-dye process called tsutsugaki. The result is a colorful, boldly outlined graphic design that easily stands out amongst the joyous chaos of the huge crowds that gather during celebrations.

Uzumaki (Swirl)

Uzumaki (Swirl)

By Yamaguchi Ryūun (b. 1940)

Bamboo

Heisei period, 2011

20.5”h x 23”w

Museum Purchase funded by Wisdom Ring Members

2015.001.007

Highly sculptured baskets like this one are formed using the three basic construction methods of twisting, braiding, and knotting bamboo – which Japanese basktmakers having been using for centuries – but in the last century and a half, artists have been creating dynamic, contemporary forms that go beyond mere function and highlight self-expression. Uzumaki is a stunning example of how a simple form made only of one material can be shaped into something that implies active motion and expresses an artist’s individual perspective. In Yamaguchi’s own words:

I express beauty through bamboo: the beauty of water flowing, the beauty of flowers, the beauty of moving clouds. I try to bring the beauty of nature into my sculpture.

In 1963, Yamaguchi began as an apprentice to Shōno Shōunsai (1904-1974), who in 1967 was designated an Important Intangible Cultural Property holder by the government of Japan. This apprenticeship inspired him greatly to achieve the same artistic status as his mentor.

Tops (Edo-Goma)

Tops (Edo-Goma)

By Hiroi Michiaki (b. 1933)

Paint on lathed-turned wood

Shōwa period, 1970-1989

(L to R) 8.75”h x 5.5”w; 12”h x 7.25”w; 6”h x 3.5”w

Gift of Janell J. Landis

2014.019.076, 2014.019.101, and 2014.019.099

During the Edo period (1600-1868), itinerant acrobats began to incorporate spinning tops into their performances, balancing them on the blade of a sword or on a fan. As this novelty grew in popularity, more and more artisans began to make tops for individual use or as ornaments. The tops became known as Edo-goma, referring to the city of Edo (now Tokyo). These clever and amusing devices became so coveted by the aristocracy that the style of the tops available to more modest classes was restricted by governmental edict. Like other visual artists, top makers found creative ways to maneuver around censorship such as designing a wider variety of Edo-goma and incorporating some of the same slyly subversive characters seen in paintings and prints of the time.

These Edo-goma were all created by Hiroi Michiaki (b. 1933), a fourth generation maker of Edo-style tops. After a childhood spent in Tokyo, Hiroi moved to Sendai where he established himself as an independent artisan, learning and teaching the craft of traditional Edo-goma. Beautifully turned out of wood and meticulously painted, each top is a wonder of design and kinetic engineering. In addition to standard tops, the subjects of Hiroi’s work include gods, demons, priests, folklore heroes, mythological beasts, and ordinary humans engaged in whimsical repetition. According to the artist, his intent is simple: to entertain and share the joy he feels in creating Edo-goma.

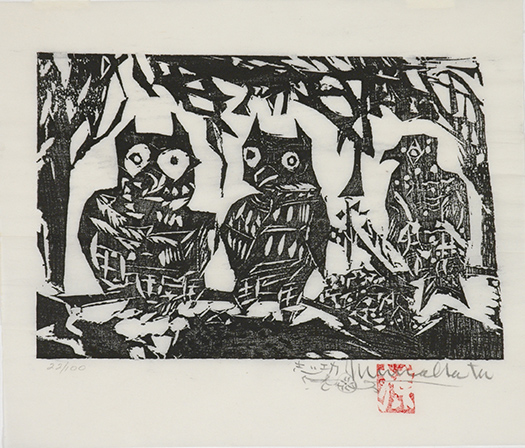

Gathering of Night Birds (Yachō Domo no Saku)

Gathering of Night Birds (Yachō Domo no Saku)

By Munakata Shikō (1903-1975)

Woodblock print; ink on paper

Signature: Munakata; Seal: Muna

Shōwa period, ca. 1967

7.5”h x 11.5”w

Purchased funded by Members of the Wisdom Ring

2015.001.001

Munakata Shikō is regarded by many Japanese and Westerners as one of the greatest modern woodblock print artists. Born in the snowy northern prefecture of Aomori, he was brought up to learn the Munakata family trade of blacksmithing. As a young man, he became interested in Western style oil painting, developing a particular devotion to the study of Van Gogh. Although his talent gained some recognition, he was never quite accepted as a Western painter. Ultimately, he turned inward and sought to discover the essential elements that were unique to Japanese art. Munakata became convinced that the woodblock print, or hanga, was the key to bridging Japanese traditional art and the international world of modern art. His revolutionary approach to printmaking eventually earned him great accolades at home and abroad. Munakata was the first Japanese to win the Grand Prix at the Venice Biennale in 1956.

Throughout his career, Munakata created prints for a variety of purposes, including commercial partnerships. When the marketing manager of Yaskawa Electric Company met Munakata in the 1950s, he was so taken with the energy, charm, and universal appeal of his work that he commissioned the artist to produce a series of twelve prints for a company calendar. One of the prints from the series, Gathering of Night Birds, is shown here. The bold, improvisational approach to drafting and the jagged carving of the woodblock demonstrate the rebellious exuberance characteristic of Munakata’s style.

Funded in part by PNC Art Alive, The Japan Foundation, New York / Center for Global Partnership and the Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Charitable Foundation.