Autumn Leaves 紅葉

In South Florida–where you’ll find the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens–the seasons are not as distinct as they are in Japan. The archipelago nation stretches from the tropical islands of Okinawa in the southwest to the snowy islands of Hokkaido in the northeast. On the main island of Honshū, the seasons are more temperate and stable.

All the seasons are important in Japanese culture. The subtle changes of nature are tightly bound with literature, poetry, painting, ceramics, incense, flower arranging, and all the arts that demonstrate Japanese principles and aesthetics. In fact, every five days is considered a micro-season, indicating a very specific point in time for those familiar with the system. For example, the phrase, “plums turning yellow,” would indicate mid-June. On the other hand, “salmon gathering to spawn” would be mid- to late December.

Equally as popular as cherry blossom viewing in spring, autumn foliage viewing (or momiji-gari) and moon viewing (or tsuki-mi) in autumn are eagerly celebrated. Both activities help the viewer to focus on the impermanence of the changing world around us. What other sites and sounds remind you of autumn?

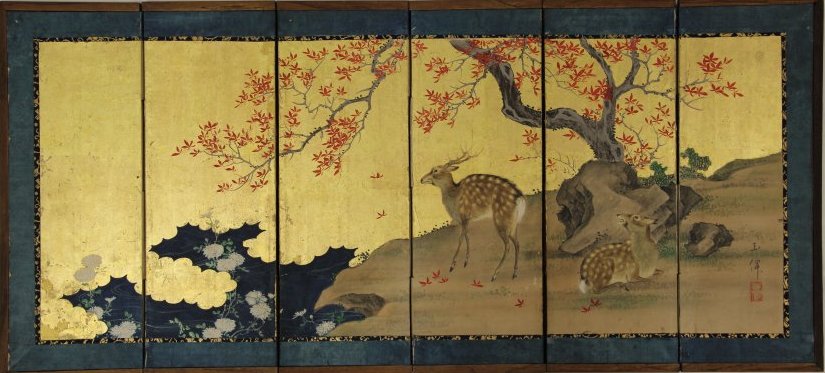

Illustrated folding screen (byobu-e)

Gold leaf works well with Japanese pictorialism, with compositions that use abundant unpainted space or negative space in which the metallic qualities of the gold, its iridescence, and its ever-transforming, transmogrifying refraction of light are showcased to full effect. One might also note that many times when a screen is placed in a Japanese interior according to pre-modern lighting conditions, it extends whatever natural light or candlelight is in the room and really transforms it. There is this fractal effect on the surface of a gold screen because of its gold foil, which can often take on an organic and uneven effect across its surface. The topography of a gold screen is ever-changing, and this is reflected in the light that it gives off. So the gold foil was both an empty background and a kind of decorative surface that interacted in a scintillating way with the actual space of the room, but also with the viewers’ imagination.” –by Yukio Lippit, professor of art and architecture at Harvard University.

This screen is paired with another that depicts a spring motif.

Dōshin and Young Ishidōmaru under Maple Leaves from the series Twenty-Four Imperial Accomplishments

A man steals away to a temple on Mount Kōya and there enters the priesthood, taking the name Karukaya Dōshin. Maki no Kata (his concubine) and her 2-year-old son Ishidōmaru wander in despair around the country looking for him, but to no avail. Several years later, they learn that he might have entered the monastery of Kongōbu-ji temple, where women are strictly forbidden to enter. Maki no Kata asks Ishidōmaru to make inquiries and tells him how to identify his father. The boy climbs the mountain, and when he meets a priest, he asks him about his father. The priest denies any knowledge of him, but Ishidōmaru notices a mole over the priest’s left eye. He exclaims that his father has a mole in the same place. The priest, overcome with love for his son, is tempted to reveal his true identity. However, remembering his vow never to see his relatives again, he conceals his feelings. He turns away heartbroken, leaving the boy in tears, which is the scene depicted here by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka. –from The Hundred Poets Compared: A Print Series by Kuniyoshi, Hiroshige, and Kunisada by Henk J. Herwig and Joshua S. Mostow, 2007.

Yoshitoshi is generally considered the last great master of the Japanese woodblock print (ukiyo-e) – and by some, one of the great innovative and creative geniuses of that artistic field.

Young Geisha (Maiko) in Autumn

Maiko are the apprentice geisha still training to perfect their cultural and entertainment skills. Maiko outfits are more eye-catching to divert attention from the lack of knowledge and experience. Geisha’s fashion is usually more mature and subtle. Maiko must live in the “mother’s” house and depend on the little stipend she receives from the geisha house. On the other hand, Geisha are more independent and can live in separate houses in the geisha neighborhoods. –from Geisha, by Liz Dalby, 1983.

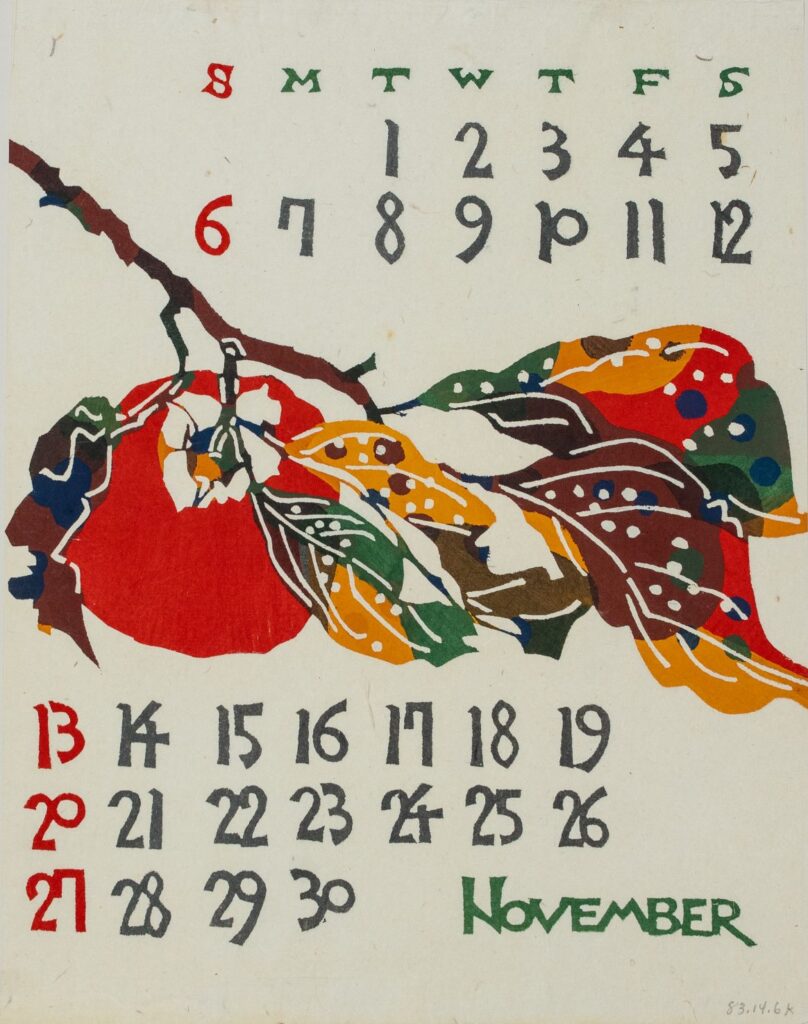

Calendar

Woodblock prints were initially used as early as the eighth century in Japan to disseminate texts, especially Buddhist scriptures. The designer and painter Tawaraya Sōtatsu (died ca. 1640) used wood stamps in the early seventeenth century to print designs on paper and silk. Until the eighteenth century, however, woodblock printing remained primarily a convenient method of reproducing written texts.

In 1765, new technology made it possible to produce single-sheet prints in a whole range of colors. Printmakers who had heretofore worked in monochrome and painted the colors in by hand, or had printed only a few colors, gradually came to use full polychrome painting to spectacular effect. The first polychrome prints, or nishiki-e, were calendars made on commission for a group of wealthy patrons in Edo, where it was the custom to exchange beautifully designed calendars at the beginning of the year. –MET Museum, Time Line of Art History.

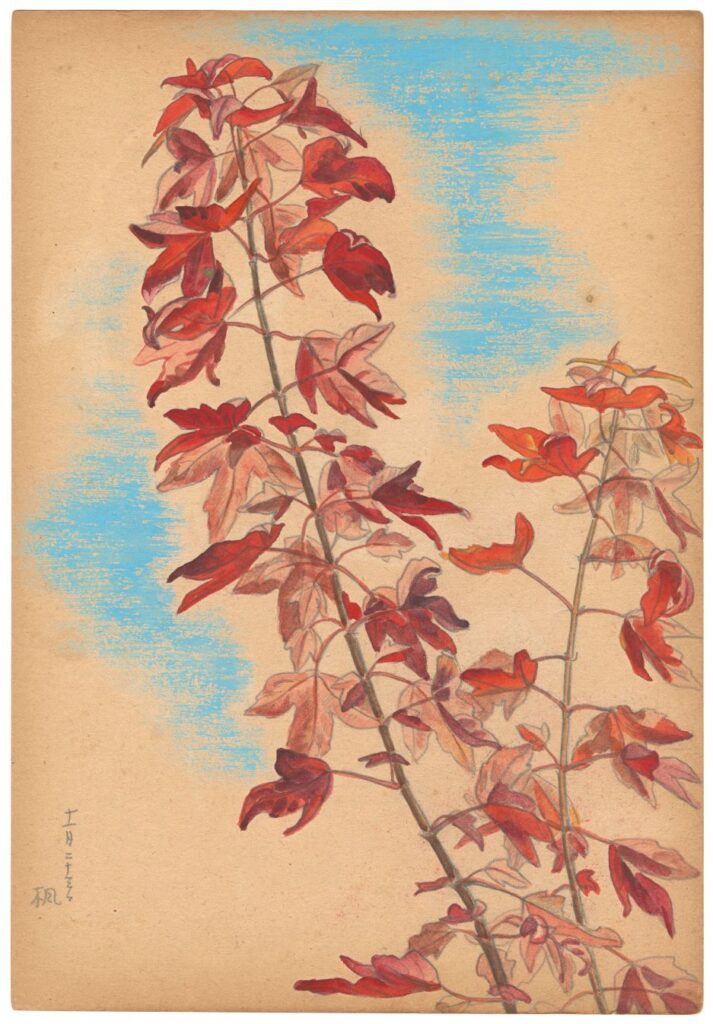

Drawings

Inagaki Tomoo is best known as a Japanese print artist who portrays playful cats in abstract compositions. He was a self-taught artist who began making sōsaku hanga, or creative prints, in 1924. Traditionally, Japanese artisans created woodblock prints in a studio system involving several artists and a publisher to produce one piece. By the early 20th century, there was a new movement of individual artists making their own prints from design concept, to cutting the woodblocks, inking the woodblocks, printing, and distribution of the final product.

Inagaki was one of these innovative artists. In the Morikami Museum Collection, we have a large grouping of notebooks, sketchbooks, drawings, paintings, and small-scale prints that demonstrates his versatility as an artist. The selection of over 100 items was a gift from William and Roberta Stein, owners of Floating World Gallery in Chicago. Some of the drawings and paintings are dated and range from 1923 to 1953, representing the early part of his career.

Immortal 6 Autumn – Kisen Hōshi

Kisen Hōshi was as mysterious in life as he is in this print. While it is certain that he was a Buddhist monk who lived in the mountains of Uji, southeast of present-day Kyoto, during the early Heian period (794–1185), the exact dates of his life are unclear. In the print, Kisen Hōshi wears a tan-and-green patterned monk’s robe draped over his dark, plain clothing. He holds a fan and glances over his shoulder at the viewer, smiling but not divulging the reason for his mirth. There are only two poems that can be attributed to him, the most famous being:

Wa ga io wa My hut is

miyako no tatsumi to the southeast of the capital

shika zo sumu where deer live

yo wo ujiyama to in the Uji mountains

hito wa iu nari or so the people say.

-Yale University Art Gallery

This print is part of a larger donation of 54 works by Otsuka Hisashi from Bruce and Susan Arbeiter.

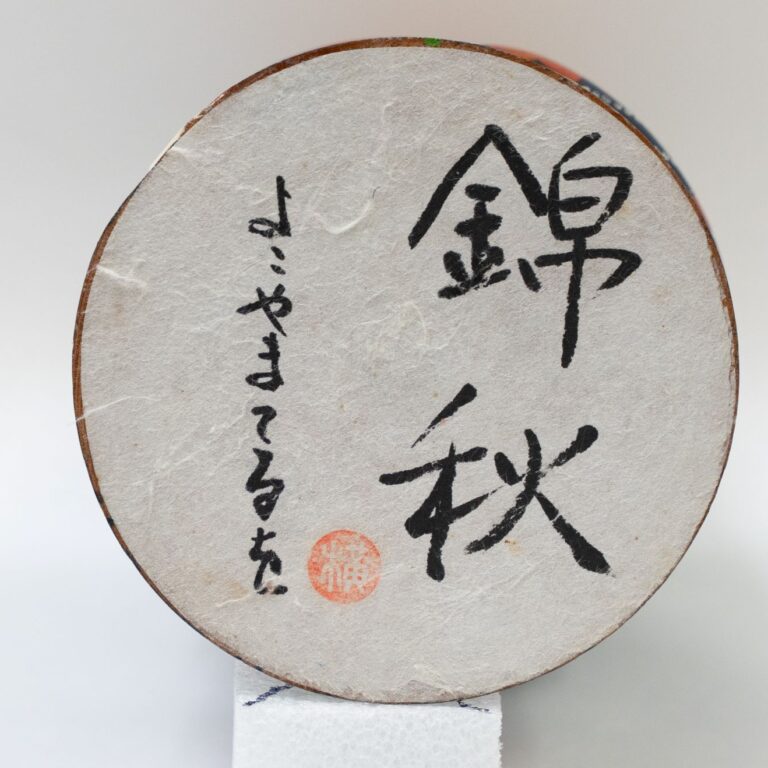

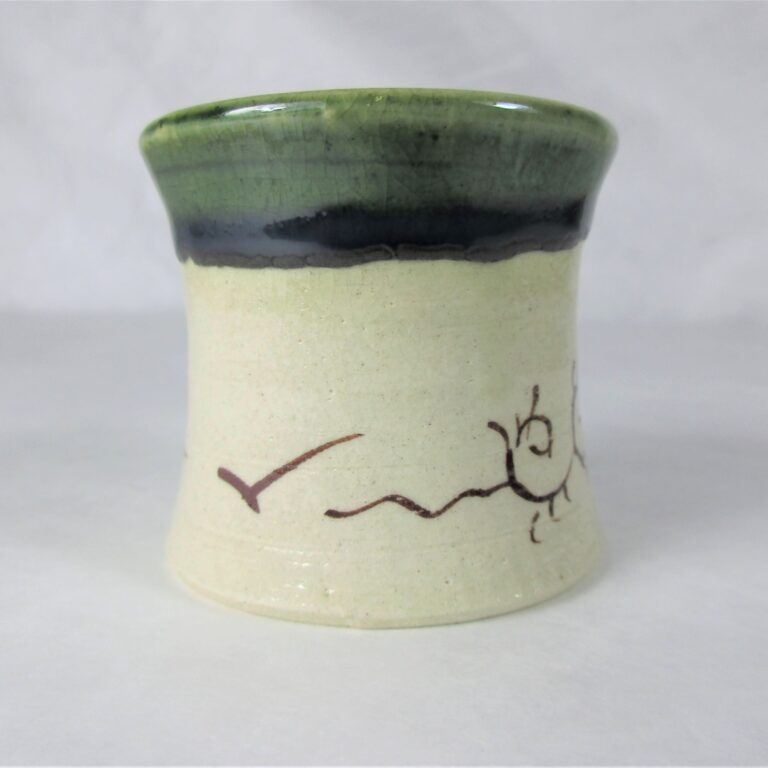

Brocade of Autumn doll

The earliest kokeshi [pronounced kō-kê-shī], had limbless cylinder-shaped bodies with round heads. In terms of design, kokeshi remained virtually unchanged until the early 1950s, when artists began experimenting with a variety of materials and techniques. Artists transformed kokeshi into myriad shapes and sizes and imbued them with fanciful expressions and decorative surface treatments. The Robert “Bob” Brokop Collection at the Morikami Museum is comprised mostly of these post-1950s kokeshi known as sōsaku kokeshi (sōsaku meaning creative). Sōsaku kokeshi differ from their predecessors in that they are more artistically sculpted in terms of silhouette and surface decoration.

Bob Brokop’s collection comprises a wide variety of such kokeshi which can be categorized by certain features. These include hair-blowing-in-the-wind, hourglass-shaped and composites made up of wood pieces assembled together using glue and wood dowels. There are intimate kokeshi representing amorous couples and familial ones that consist of mother and child pairs, tenderly expressing and eliciting familiar human sentiments. –from “An Introduction to Bob Brokop and Sōsaku Kokeshi,” Susanna Brooks, 2013.

Doll with stripes and maple leaves

Sekiguchi Sansaku (born 1925, Gunma Prefecture) began his artistic career as a Japanese painter. His paintings were awarded top prizes in several juried exhibitions from 1951 to 1957. The following year, in 1958, Sansaku devoted himself entirely to creating sōsaku kokeshi, garnering many prizes for his work. Many of his kokeshi are held in the collection of the Corfu Oriental Museum. In 1978, he was recognized as an outstanding creative kokeshi maker and was designated a Holder of Excellent Technique. In 2008, Sansaku received the Contemporary Master Craftsman Oju Medal of Honor. -mingeiarts.com